A 'Virtual Panel' Webinar by #DesignPopUp Net Zero Carbon Design & Sustainable Architecture

The latest in our series of #DesignPopUp webinars took place on Thursday 10th December and, judging by the audience participation, was the most successful yet. Speaking on the topic of Net Zero Carbon Design and Sustainable Architecture in the education sector, four panellists put forward their views, experiences and projections.

The Panel

The speakers were: Lee Bennett, Partner, Design Chair and School Design Lead at Sheppard Robson Architects LLP (top left); Dr Sharon Wright, Senior Associate at the learning-crowd (top right); Mark Skelly, Director, Skelly & Couth Ltd (bottom left); Dr Stephen Finnegan, Zero Carbon Research Institute, Liverpool University School of Architecture (bottom right).

Architects & designers must take urgent & ambitious action

With the UK Government setting a strategic goal of developing Net Zero Carbon buildings by 2050, architects and designers must take urgent, ambitious and immediate climate action towards decarbonising the built environment. Net zero carbon no longer refers only to a building’s operational use, but also to design and construction, which can account for half or more of all carbon emissions.

The discussion, therefore, centred around how architects and designers can create low carbon buildings and interiors, considering all areas of the supply chain, sourcing and construction processes, in order to improve the whole life carbon footprint of a building and secure the environmental future of our planet. Given that schools are government-funded, the education sector seems a logical place to begin.

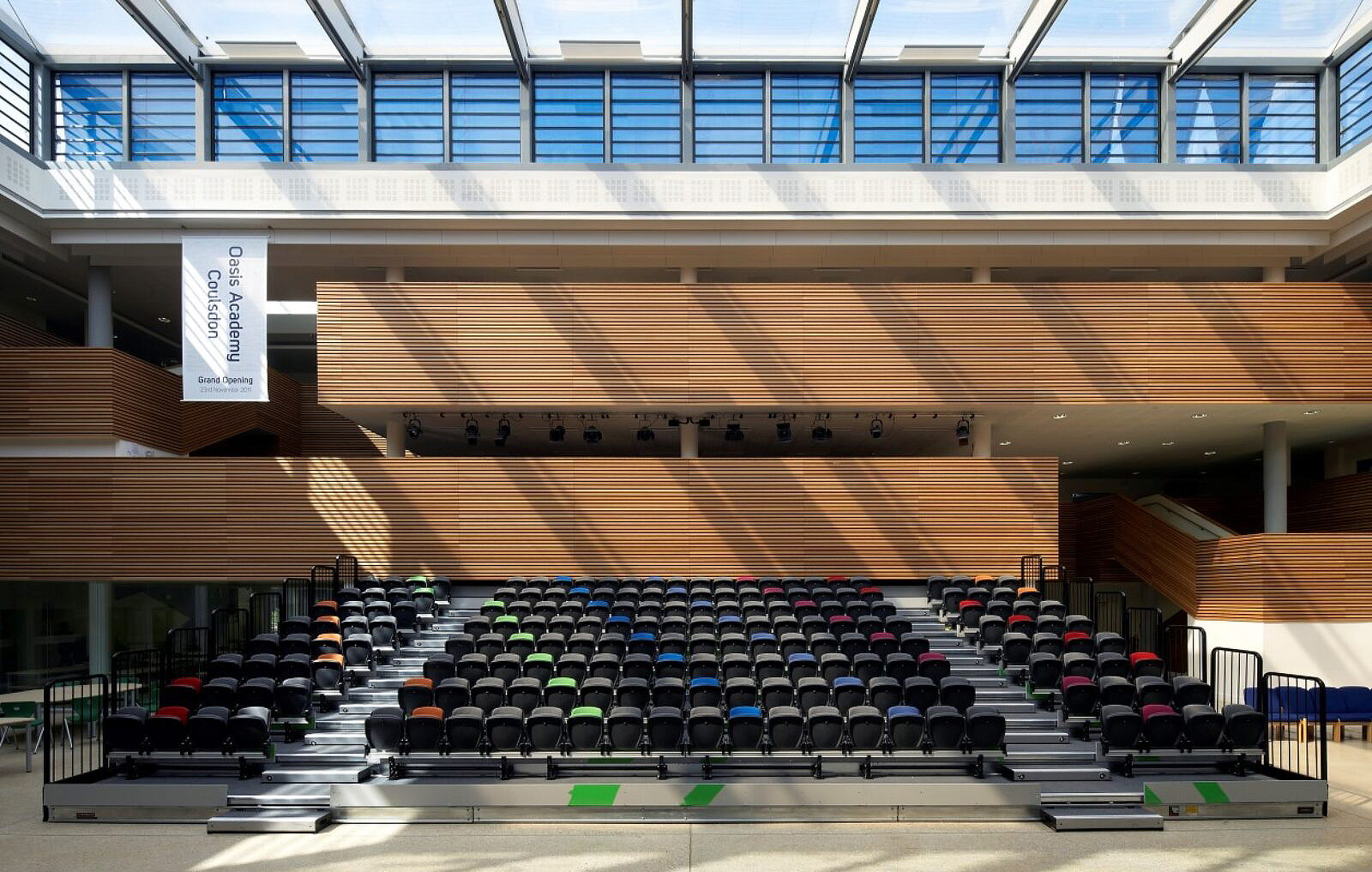

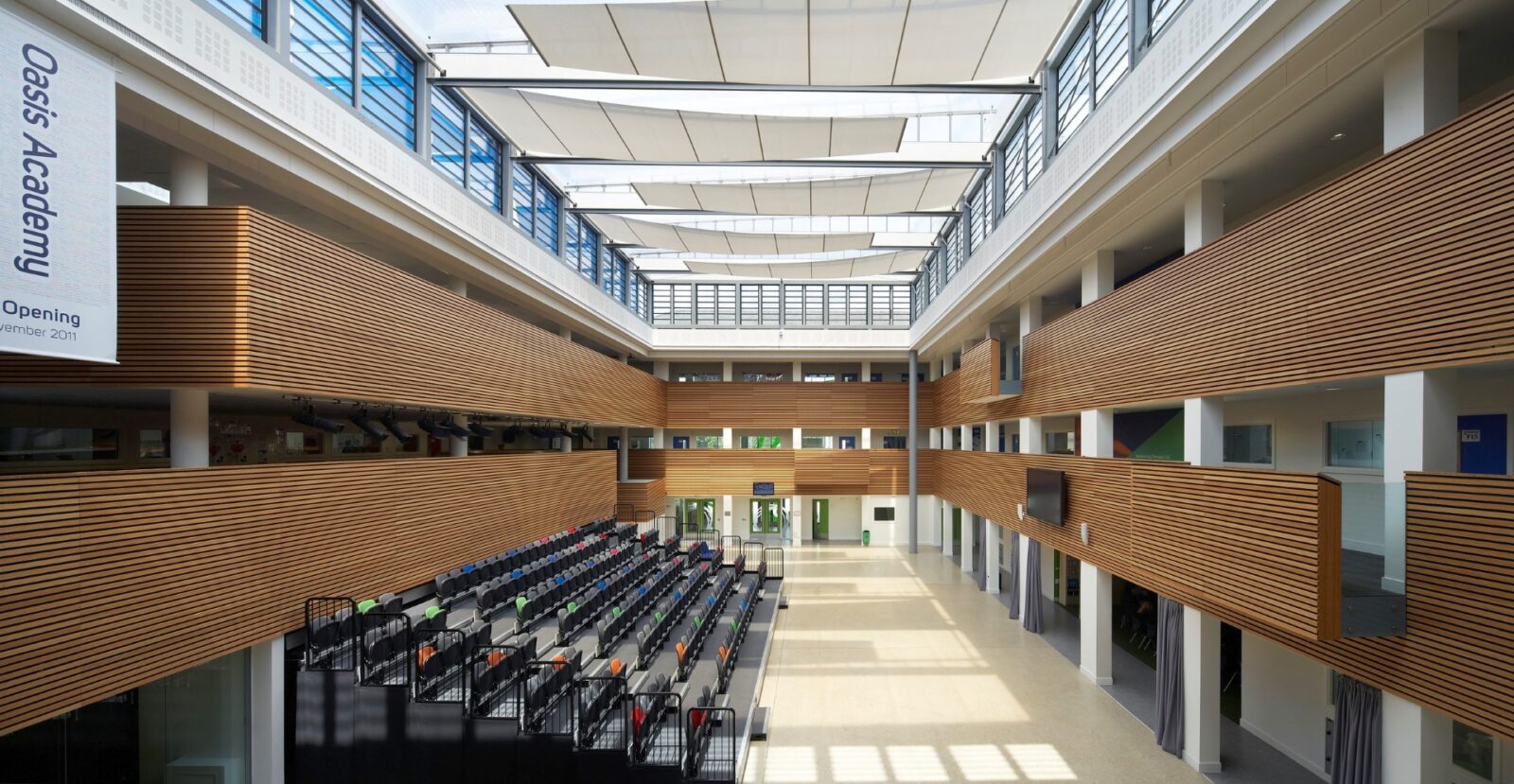

Project Image: Oasis Academy, Coulsdon, Surrey. Design by Sheppard Robson.

“Globally, construction accounts for around 19% of carbon emissions, but in the developed world, it’s around 40%. Therefore, it’s even more important that we in the UK take on this responsibility because our impact is higher.”

– Lee Bennett

A global responsibility with many challenges

Reaching the stretching targets set by UK government will be no easy task. The panellists all agreed that while having targets in place, and a united focus on sustainability, is a good thing, it’s hard to meet targets when the regulations, measures and approaches which currently exist are all so disparate.

“The question,” said Lee Bennett, “Is whether schools, in terms of a large-scale building programme for the UK, can lead the charge, representing the whole of the construction industry.” But he points out that despite a profusion of declarations of intent from bodies such as the UK government, the RIBA 2030 Climate Challenge, Architects Declare and others, there is no cohesive policy which tackles both operational and embodied carbon use. Likewise, there is no consistency in the metrics in place to measure carbon emissions or environmental impact, nor in the methods and processes that will help achieve the goals.

The panellists all suggested that the education sector is a great place to start; not only because schools are government-funded initiatives, but also because of the need to embed sustainability within the mindsets and approaches of a new generation, and to extend the role of schools within their communities to the collective benefit of society as a whole.

“There is a lot of debate around this topic and a massive push toward carbon neutrality by bodies such as city councils, big corporations and governments. But we need to understand what it really means and how to get there – and the biggest elephant in the room is cost.”

– Dr Stephen Finnegan

The importance of carbon literacy

One of the major challenges, as outlined by the panel, is the lack of cohesion across NetZero policy-making and distinction between operational and embodied carbon. Part of the reason for that is a lack of education in the subject – a lack of carbon literacy, as the panel termed it.

Dr Stephen Finnegan explained the difference between the two distinct areas. Operational carbon – how we heat, cool, power and fuel a building – is further ahead in terms of policy and action. The UK government has targets in place for all new buildings to be fully electric by 2025 (although there is serious doubt that those targets will be reached), and renewable energy is already firmly in the spotlight.

Embodied carbon looks at the whole life impact of products and materials, including sourcing, transportation, assembly, manufacture, end of life planning etc. It is, therefore, more complex to measure and prove; and yet the UK government targets are equally stretching, with a 40% reduction expected by 2030 and a challenging 100% reduction required by 2050.

Only by looking at the combined impact of both areas, taking a truly “whole-life” approach to design and construction, will significant improvement be made. The panellists discussed that, although this is nothing new, it is becoming increasingly urgent.

“It’s known that we take a fabric first approach, i.e. insulating well, designing efficient buildings, to reduce the need for more energy in the first place,” said Dr Finnegan. “And we look at how we source that energy. Renewable sources are of course preferable, but there are questions around storage when you’re reliant on solar or wind power. With embodied carbon, we must look not only at the types and volumes of materials we use but the whole life impact of them. And for that, we need more consistency in how that impact is measured.”

Measuring environmental impact is problematic & inconsistent

Dr Finnegan highlighted the issues with environmental impact metrics, stating that without a consistent, benchmarked set of measures in place, it will be almost impossible to introduce meaningful universal standards. The introduction of Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) is designed for exactly this purpose, establishing the environmental impact of a product in terms of CO2 and other greenhouse gases, as well as factors such as acidification, abiotic depletion rates etc.

“EPDs will be critical for this process,” he said. “But it’s early days. At the moment the process is fundamentally flawed because there are various opt-outs for classifying products, so not everything has to be included. Until there is a consistent requirement and way to measure impact, EPDs cannot fulfil their potential. But when we get them right, they will be a crucial tool for measuring environmental impact.”

A longer-term mindset for buildings is crucial

“The greenest building is the one already standing.” Lee Bennett

An important area for discussion was that of taking a retro-fit first approach, working with existing buildings to repurpose or improve their existing environmental qualities.

“Buildings have become a consumable product in a large part of the industry,” said Mark Skelly. “Big, capital-driven residential and commercial development have spilled over a bit into education. People are always looking for the cheapest way to deliver a project, and that is causing some major issues.”

In light of major crises such as Grenfell, as well as a bigger push for climate change, the Construction Industry Hub has issued a new values-based framework for costing new projects, rather than solely focusing on cost. This is based on five pillars, looking at natural, social, human and manufactured costs, as well as the actual financial outlay.

“There are many learnings to take from the way things were done in the past,” said Mark. “Look at Victorian buildings. A lot of them are still standing today; what started off as a school might now be used commercially or for accommodation. How many of the new buildings going up today could be repurposed in that way? Maybe that’s where we need to be focusing our attention. And the greater the amount of embodied carbon used, the greater the need to ensure that there is a future purpose, and multiple potential uses.”

Lee agreed, using the example of a Liverpool scheme of locally designed and produced schools to illustrate the point. The brief was based around what would happen to the buildings if they were no longer needed as a school. The solution was a series of off-site produced, modular buildings built from a hybrid of steel and glulam (glued laminated wood), arranged around a central outdoor play area. Designed primarily for use as a school, taking into account all the technical specifications for designing learning spaces, the intention was that the basic structure would be easy to repurpose in future, to anything from an ice rink to a warehouse or housing. “I could envisage this being repeated nationally, and it was a real success in Liverpool,” he added.

Adaptability, then, is a crucial element of designing for longevity. As we move towards low energy buildings and lowering the proportions of embedded carbon, it is also important to consider future uses for the buildings being designed today.

“Building in concrete is like drawing with a permanent marker; every stroke needs to be very carefully thought through. Building in timber is more like a pencil, which can be rubbed out and repurposed. So perhaps we can think more about using a permanent core and then building around it in other materials which are easier to adapt over time.”

– Mark Skelly

Modern Methods of Construction (MMC)

“MMC is working to a new framework for 2020-25 which suggests that for all primary, secondary and SEN schools, a component-based approach should be taken, targeting 70% off offsite construction, using panelised and volumetric system builds. Timber offers less waste, lower carbon and a quicker build. Timber has a great role to play in sustainable construction and in many cases, offers the ideal solution.” Lee Bennett

MMC looks to minimise environmental impact in three ways; by making improvements in on-site and off-site processes, and by carbon offsetting, which should be seen as a last resort. The key is finding efficiencies of process and power throughout the entire supply chain, factoring in every element of sourcing, manufacture, transport and so on.

So how can MMC minimise waste and create a greener and more sustainable solution? According to Lee, the first point when thinking about the state school programme is to have a solution which can be repeated, something scalable and adaptive.

He believes a modular system from cross laminated timber (CLT) is ideal, as it not only has low embodied carbon in terms of the materials, but much of it can be produced efficiently off-site; there is also less waste, less time and disruption on-site. The aim is therefore that going forward, 60% of new build stock will be done under MMC.

He said, “This is only really sustainable if we go down a predominantly timber route. The operational carbon impact can be largely solved using good insulation and air flow design, but we need to be thinking harder about the materials that constitute the base materials of the buildings.”

So is timber the answer?

Timber was discussed at length by the panellists who unanimously applauded its inherently sustainable qualities. It not only looks great; it ticks a lot of boxes for durability, safety and sustainability.

“Timber offers minimum waste of space and of materials, and has been proven to have a really beneficial effect on students as well,” said Lee. He cites a year-long study conducted at the Joanneum Institute in Graz in 2009, comparing the performance of students in a plasterboard classroom with that of students in a mass-timber classroom. “Children were less stressed, less aggressive and more relaxed, and their academic performance went up. There is a whole sensory experience with timber, not just the visual – it’s the texture, the smell, that really links together the human relationship with the outside world,” he said.

But there are problematic perceptions around the mass usage of timber which our panel says need to be addressed.

“When we told people that a particular school used 7000 trees, they were shocked,” said Lee. “But the fact is, cellulose grows incredibly fast. In fact, those 7000 trees were replaced in just one day.”

“Timber must come from sustainable sources,” agrees Mark Skelly. “In countries like Finland and Austria, they have a really sustainable rotation in place which doesn’t affect the carbon sequestration long term like in the UK. We are currently only plugging only 30-40% of Europe’s wood resources. Sustainable forest practice is really important as a central part to this whole discussion.”

Timber is also often associated with fire risk, which both Lee and Mark were quick to address.

“Timber is remarkable,” said Lee. “It actively protects itself in case of fire – it chars, which slows the burning process. Fire retardant treatment has come a long way as well.”

Mark agrees, adding, “Timber itself is often not the problem. But we often see timber-framed houses which are then clad in plasterboard and other materials. This is often where the real issue is – we don’t always get enough time to design as efficiently as we could, so end up using more materials than are necessary. If you had longer you could, in theory, find ways to use less material. The industry needs to get more up to speed on the technicalities of designing in timber, especially as we start to look at future climate scenarios, beyond 2050. Timber is not necessarily the answer for all construction projects, but it is particularly well suited for schools in the UK.”

“It is not enough to just innovate. You can’t just put buildings down and expect users to know how to use them and unlock all the benefits fully – there needs to be more guidance from designers to help the end-users optimise that potential and use the buildings properly.”

– Dr Sharon Wright

The vital role of Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) in narrowing the performance gap

“It is not enough to just innovate. You can’t just put buildings down and expect users to know how to use them and unlock all the benefits fully – there needs to be more guidance from designers to help the end users optimise that potential and use the buildings properly.” Dr Sharon Wright

“POE is absolutely critical,” agrees Dr Stephen Finnegan. “There is not currently enough information on this. Some studies are currently quoting a difference of up to a 40% performance gap between what was promised and what is actually happening in terms of emissions and fuel efficiency.”

The ongoing use of buildings and resources should also be part of the curriculum and student learning, according to the panel. Dr Finnegan says, “I believe there is a role for schools to play in offsetting their own carbon footprint. Schools create around 200 tonnes of carbon emissions per year – how might they be able to reduce this? And how could those learnings be applied to local businesses? Schools may even have a role to play in helping with local offsetting of resources, or storing renewable energy. There’s an interesting discussion to be had there.”

“As a society, we need to look at how we live our lives and how much energy we consume. Younger people are honing into that far more than older generations, and lockdown has really focussed attention on what is absolutely necessary and what isn’t. It will be interesting to see the longer-term impact of lockdown on society’s attitudes to sustainability.“

– Mark Skelly

Sustainability will rely on lifestyle and mindset – not just construction

Tapping into the potential for younger generations to contribute to sustainability was seen as key. Dr Sharon Wright discussed examples of how Wales and Scotland are addressing sustainability at the core of education policy, with the aim of creating responsible citizens who will contribute actively to society and the environment.

“I believe there needs to be a real drive towards embedding sustainability within the purpose of a country’s curriculum, in order to engage young people to empower them to become part of the solution, and use education to drive an awareness of real-world problems like transport, supply chain, energy and so on,” she says.

“There is a real potential to make a difference. Health and wellbeing are finally on the agenda when talking about schools and the curriculum. The pandemic has really focused attention on the importance of outdoor spaces, biophilia and community. Schools are not just somewhere for students to learn – they should also be seen as community hubs, and of course as a workplace for staff. They have a big role to play and there is a responsibility to ensure that sustainability is embedded at the heart of policy.”

The panellists all agreed that young people are clamouring for more involvement, and that there is a great appetite for activism and change. Finding ways to engage with that energy and potential to help them influence and be heard, to encourage more involvement in STEM and actively involve young people in coming up with solutions, will be vital.

“We tend to think of schools being quite self-contained entities, separated from the outside world,” says Dr Wright. “But we should think of schools in a wider context, looking at how they interact with their communities, using more joined up thinking around transportation, heating, energy storage etc., and involving the community to see the benefits that school can bring to society.”

“We don’t have all the answers at this point. This is only the beginning of the conversation, and there is a very long way to go.”

– Dr Stephen Finnegan

A five-point plan for an improved sustainability legacy

While the answers are not yet known, the panellists agreed that the principles of approach should be aligned and agreed, with improved measurability and consistency across the entire construction sector, not just in education.

Lee Bennett shared his own five-point plan:

- Retain and revive: the importance of retro-fit and improving what already exists

- Fabric first: adopting a timber-based strategy wherever possible

- MMC initiatives of 60% by 2040, which could (and should) incentivise timber

- Wellbeing and whole life value to be major considerations as measurable positives

- Pedagogy: initiate a nationwide Learning for Sustainability STEAM policy and encourage “learning for life” to sustain meaningful life on this planet

While guidelines and regulations are starting to improve, there is still a long way to go in standardising the metrics around sustainability and the targets are going to be a real challenge to hit. Without benchmark measures in place, hitting targets is even more challenging.

Designing for the climates of the future

The world’s climate is changing, and modelling is already underway for designing buildings suitable for the climates predicted post 2050 or 2080, with much higher average temperatures in the UK. Timber doesn’t always perform as well in higher climates – although it has the potential to - so there is a lot of work to be done to meet the likely demands of future climate requirements.

The need for carbon literacy is even more acute when considering longer-term design, as there is a danger of simply shifting carbon from one area to another rather than achieving a real solution. From the ultra-efficient principles of the “Passive House” design to innovations in materials and methods to reduce embodied carbon, all considerations are already under investigation when looking at designing for the future.

“A brief for a school often starts with practicalities like, how many classrooms do we need and how do we heat it. But what if that conversation began with asking how students, staff and communities could use that resource to flourish – what might that look like?”

– Dr Sharon Wright

Pushing sustainability up the agenda from the outset

In order to make a significant change, the panel agreed that there needs to be a shift in mindset across the design and construction industry, and in society as a whole. Part of that shift could take the form of changing the initial scope and brief for new projects from the outset.

The speakers suggested that if factors such as carbon costing, long-term adaptability, purpose, wellness and user satisfaction, embodied and operational impact and POE preparation were all considered and built into a brief upfront, the outcomes might be very different.

“A brief for a school often starts with practicalities like, how many classrooms do we need and how do we heat it,” says Dr Wright. “But what if that conversation began with asking how students, staff and communities could use that resource to flourish – what might that look like?”

The panel also suggested that more resource be committed to finding new, or at least improved methods and materials.

“We don’t often have time, particularly on state school projects, to explore and prove alternatives – and that’s a real barrier to use,” says Lee Bennett. “A classroom is a technical challenge, and there tends to be a “go-to” set of products which we know are safe to use. So when we’re looking at new materials, recycled materials, or even timber, there are barriers because of the time and budget.”

A safe bet may be easier and cheaper in the short term but for real change, the panel suggests that the scope of thinking needs addressing fundamentally. Whether that’s taking learnings from the past and re-introducing skillsets and supply chain capability to use older products like clay plaster, or looking to new methods, materials and innovations, the panel agreed that only with real focus and investment will significant and sustainable change be made.

Strong themes in the future of design

Over the course of this series of webinars on the future of design, certain messages are beginning to emerge loud and clear.

The need to engage the younger generation through education is very apparent, giving them a voice and an opportunity to influence and shape their futures. Rethinking fundamental approaches to a building’s purpose right from the start, incorporating flexible, adaptable elements to allow users to determine shifting purposes over time should also enable longer and more efficient uses.

The pandemic has intensified many of the messages, but none so much as biophilia, and the importance of incorporating the natural world into design. The trend of bringing the outside in looks set to continue, supported by technical developments in materials that can enhance the flow between indoor and outdoor spaces.

Sustainability is arguably the core element, and needs to be considered in all its meanings, from longevity of design to environmental impact and whole life considerations not just of materials, but processes and methods of construction.

The emergence of these vital themes underlines why it is so important that conversations like this are continuing to happen, and the message must be amplified across all sectors to really take root. Design, architecture and construction are pivotal to a sustainable future, but the actions, attitudes and initiatives of every individual will feed into this evolution as well as we work towards finding new ways to design our collective future.

We look forward to welcoming you to the next webinar in this fascinating series in February, when we will be looking at the future of design in the workplace.

This virtual event took place on

Thursday, 10 December 2020 at 10.30am.

But you have not missed out,

you can catch up with the video recording.

Visit our showrooms

Share this news